|

UNDERGROUND VOICES: FICTION

|

|

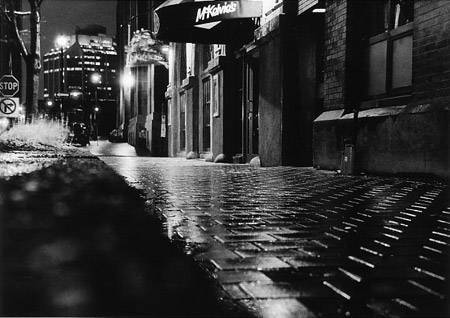

TOM BADYNA Yo Yo Yolanda I can't start a story with "It was raining," though it was, and that's important because all my life

So that was part of it. The cold and drizzle and gloomy dusks that commenced in mid afternoon put romance in my soul, but of a particular kind, the kind you knew you weren’t gonna get right. And I hungered for it still.

#

It was raining. I remember that. And it must have been a Saturday, as there was radio opera on three stereos in distant places in the long, narrow bays of the old warehouse. Water dripped. Birds – you heard their wings and it made starts in your heart. But not when the opera was on. I drank rich coffee by the rusting woodburner whose flue I'd rigged into a suspect chimney. I poured whiskey in the coffee and tended the fire and ignored my life and listened to the Bellini opera sound distant and close, ethereal, haunted with its own loveliness as it filled the whole of those abandoned spaces. This was how opera should sound, Bellini's anyway, with the harmonics of his long melodic lines shifting into remote keys. You didn't need ten grand for a Bang and Olufsen and engineered walls in a room suitable for Architectural Digest. Opera – trust me – was better in the wilds of a leaking, high-ceilinged warehouse on a mixed-use street in a sinking neighborhood in a Rust Belt city, if in it you placed three stereos left behind ten years apart at least, by the hippies in the seventies, the punks in the eighties and the artists in the nineties, each having succeeded and failed exactly as had all the businesses before them, and tuned each to public radio's broadcast of the Texaco Metropolitan Opera, Bellini, if possible. Opera once might have been true in glittering halls with three thousand seated on velvet, but that was a different world. It now was best like I had it, and I listened swept and transported and all that, until I couldn’t stand the loneliness no more and left and walked blocks and blocks, head bowed, hands jammed in pockets. The rain turned to sleet, and the streets froze into sheets of ice, and down the wide sidewalk five hundred feet past home, the warehouse empty and dark, I opened the heavy wood door of the corner bar, which had on one side of it the cold, deserted street and on the other side – warmth. Brightly lit knotty pine and Mexican music loud. Hipster Hispanics played pool. Their girlfriends splayed sideways in the booths. I was old to them, and white, hardly existed, which I liked and took a seat at the bar, my back to them, and drank without a thought as I watched their dramas through the gold smoked mirrors. In and out and between the bottles they played out their roles like Romeos and Juliets, Mercutios and Hotspurs. They might have been poor, with sour futures, but their eyes still batted, their hearts fluttered, and in the bar, in a hurry or something, walked a woman attractive enough. She was white, and that wasn't unusual. It wasn't usual either. But I paid her no mind as she sat a seat away from me, then next to me. She buzzed and hopped with static like she had a forty-volt transistor up her ass. Did I live around here, she asked. I said, Yeah, sort of, and talked about my dislike for football, a game of which was on the TV. Her presence did nothing for me. She wasn't it, not for me, not at this stage in my life. I could tell. And I didn't want to do anything but, after a few drinks, go home alone. Carmen had but two months gone for Los Angeles, had said she was coming back, but I knew she wasn't and she knew she wasn't. A peculiar good-bye, though fitting, as we had liked the idea of each other much more than anything real. Still, I talked to the woman next to me of disliking football as if it might play well for her. But she didn't care whether I liked football, hated it, played it, cared about nothing else. She wanted to know if there was a place nearby where she could stay. She's homeless for the night, she said. Like a hotel? I said, enjoying the ludicrosity of the idea because I didn't know whether she knew or not that Front and Western had no hotels. Even the flophouses had failed. Well, if I wanted to get us a room, she said. She had no money. She was hungry. Her name was Yolanda. She'd had a rancorous falling out with her roommate, a woman, over the sexual nature of their relationship. Yolanda couldn't do it no more, couldn't return those feelings. She didn't want to have sex with women no more. When asked by me what she did, she said that she gave massages. Yeah, OK. She had strong-looking hands, auburn hair, the thirty-five-year-old face of a tomboy puberty in the country, that kind of dark-eyed villainy. You're lying, I said silently. But sometimes ya needed the lies. Sometimes a lie, if you were looking in her eyes, was the truth. Like with Carmen's good-bye. You can come home with me, I told her. People's lives get screwed up. Sometimes ya need a bit of help. I've needed help, at times. I got food. I got wine. I got a fire. So, let's go, she said and slipped her arm through mine and pulled herself close, and I neither objected nor gave in. Let's go, she said, now tugging at my arm. I said, I'm having a whiskey here. Drink it already, then. I came here for a couple of whiskeys, to be in light and warmth and around people. I'm not gonna change my mind. So, can you sit tight for a minute? But she couldn't. She tugged at my arm, pouted, itched beneath her skin. Come on, she said, I'm hungry. And I looked then at her closely. And we walked down the wide and cold sidewalk to my warehouse. She hung on my arm, and a photograph of us then, had Man Ray been about, would have captured all of my December romances, and if Yolanda wasn't one of those, it was December, and it wasn't so bad, not being lonely for a moment. The streetlights were burning-out dim and the moon was full and out, hazy, milky white. I looked up to it and hoped to take no advantage of her, and she held close to me and, maybe, I thought, wished the same. The front door to the warehouse opened into a room sixty feet long, twenty feet wide, ceilings eighteen feet high and of plaster falling in places from its lathe. Water dripped. Wind you could hear. One wall was brick and on it hung paintings, other art work, most of a rather bizarre and surrealistic nature. The opposite wall was made of crude shelves stuffed with found objects for future art projects recently and long abandoned. Everywhere else there was stuff. Just stuff collected and salvaged as if someday, in a proper setting and with work, it might be something. Towards the back of the room was a late-model arctic tent where I slept. Yolanda looked at me suspiciously. How did you explain you lived in a set from an old particularly bizarre Night Gallery episode. She said that it was freezing in here. I didn't bother explaining, but went to the middle of the room and quickly had an intensely blazing fire which magically lit a domestic tableau, a couch, a chair, lamps, a table, a rug, and that made her happier, and when she sat at the chair by the fireplace she saw on the coffee table before her a large Tupperware bowl of leftover fruit and sweet cream dip. Her eyes widened and her hair fell across her brow as she with lightning quick fingers stuffed her face. Several times she asked if there was more dip. I offered other foods, but the big bowl of cut up fruit made her eyes as big as the moon. Meat and bread and vegetables did not interest her. I was glad to be there, glad she was there. And that night, in my tent, she offered me a piece of a chocolate bar she'd squirreled away. She said she'd clean up the joint for me, if I let her stay. I didn't answer and during the love-making I knew that us, she and I, that we were not going to amount to a romance of any kind, but we fucked a long time anyway, held close and tightly, faces averted. And it was good. This was how Eskimoes fucked the wives of their hosts, I imagined. And in the morning, readying to leave for work, I tried to wake her, but deep beneath blankets and quilts she was determined to remain, and I left, couldn't turn her out in the cold and ice. She was a junkie, I knew, which meant she was a thief. Likely she was a hooker too, though for her and for me and maybe for something else, something like mankind, I’d pretended otherwise, ignore that knowledge, but couldn’t enjoy work with a junkie in my house though I came home surprised to be glad she was here, glad too she hadn't stolen anything big or that Carmen might notice, and we talked a conversation the verbatim transcript of which you could have placed in a Poughkeepsie bungalow at five p.m. until, after a while, I said I couldn't have drugs around my life any more. She understood, but was a little sad, having spent the afternoon trying to clean up the place. She was doing it when I'd come home and was happy doing it, concentrating on the small, domestic array around the fireplace. She fixed me dinner on the fancy Weber grill with two burners on the side that, with a hose and a tub was my kitchen, and we had some wine, then she shot up, and we both kinda dozed into a nap, leaned one into the other, me tired from stacking rock in the cold and snow and she from heroin. Then she made a few phone calls from the office where I had a dial-up connection on an old computer which I used wrapped in old blankets like a homeless wretch and thought the words would be as mad, but weren't. I gave her privacy and when she came out she told me by the fire that she needed to fix herself up for a job, so she could make enough money to get a room. It was a photo shoot for a massage brochure, she said, but wasn't proud about it, so maybe she was gonna go suck dick for porn, or just spread her legs for a banana. I didn't want to know, and I led her to a room where I'd rigged cold-water plumbing and a clever array of plastic tubing and six electric tea kettles from the Goodwill Store into a sizzling shower that cascaded off a rock ledge overhang. I showed her how it worked and drank whiskey and sat on the floor and watched her transform herself. She was an attractive woman, short, light auburn hair, full chested, narrow hipped, slightly pigeon toed. She had the genetics of a mesomorph, but was thin. You could see her ribs. She had brown eyes, like everyone else's. A soul looked out. As she transformed herself from a mess to, I guessed, a porn thing, she ate Oreo cookies and drank Pepsi. I asked her if that was a heroin thing. She said it was. And then she left, and I was lonely. And four or five hours later: Bang, Bang, Bang on the steel door. I crawled out from my tent because I knew it was her. Next morning, four degrees and sunny, I took her to a rooming house on Ashland Ave. It was hard not to say things, like you can come back at night, from time to time. Or let's go see a movie, or have dinner. Or, I like you. She opened the door of my truck and looked back and I said, "Take care." She said nothing, but with the look she gave me, I didn't take it as rude.

#

That was December, early, and in the middle of January, a Wednesday at noon we gave up for good trying to work in the wind and the cold. And the forecast was for temperatures colder yet. "See you boys in a few weeks," said the boss. "Ya-ba-da-ba-do," said I, and slid off my dinosaur. I called Dickhead. He said he would be over in a couple of hours, and I went to the corner Mexican bar to have a few $1.75 whiskeys until he arrived. That was my life. That was it. On my second drink, a small woman in a big white coat and hat sidled up next to me. "Hi, cowboy," she said. "Buy me a soda pop?" It was Yolanda the Junkie. I bought her a coke. "You doing all right?" I asked. She was. She had just gotten out. “Thirty days for loitering", she said. "You're clean, then?" I asked. "Yeah." "Was it rotten?" "Detox for a while," she said. "Food sucks there," I said, inexplicably trying to let her know that I too had done short, pesky stretches now and again. "Where's my soda?" she asked. We made that kind of small talk. I told her I was killing time before going out with a friend. She looked around the bar. I said, "We're going downtown. You wanna come along?" She was all right. A junkie and a hooker, maybe, probably, had problems, but she was a human too. Some of us got some good breaks along the way, with parents, love, mentors, books dropped in our laps. Some of us didn't. Some of us liked gritty pictures of urban desolation, and some of us liked the living people who lived there. And some of us lived with them anyway, saw the intractable human dilemmas in their sorry faces, heard the idiocy and normalcy of their conversation and could never figure it all out enough to say why this and not something other. "You want company?" she asked. I recognized the street code, but decided to continue to act as if I didn't. "Hey, if you want to come along, it might be fun," I said. "I'll feed you." She thought, studied me. She couldn't figure me out. I was white and had brains of a sort not common on Front Street and Western and was working, but was living here, like this. Never Explain was a good rule of thumb when doing so would make lunacy rational, as that was the very identifying characteristic of the insane. Most everyone down here believed their troubles, their poverty, their life being squashed, was a result of some honorable principle they held to that others didn't, and I believed not a word of theirs, and didn't explain mine. Not to Yolanda. I told her I got to get going, got to take a shower. She said she needed a shower. We took our showers like a married couple. Me first, then her, nudity neither flaunted nor hid, courteous. I stood at the sink, towel about my waist, brushing my choppers, combing my mop, deciding whether to continue my strike against shaving, as my beard was getting uglier and uglier. She was in the shower – which wasn't really a shower, except what else did you call a contraption that cascaded hot water on your head from a tilted stone ledge. It was all curiously non-sexual and normal,like a married couple. Well, not quite. I watched her dress to make certain she didn't steal any of Carmen's abandoned clothes. She dallied over her makeup, and I said we got to get going. Dickhead's likely out in the big room. She said. "You want a blow job before we go?" I said, "I didn't bring you along for that. I mean, I your company's OK." She was fiddling with my belt and zipper. I didn't want her to. I wanted a wife and no blow jobs. "Go ahead," I said. She said, "Twenty bucks." I said, "Stop then." She said, "Aw, come on, I need money." She was already getting busy. "You don't need to do this. I'll feed you." She put out a hand, palm up, and I couldn't stop her from sucking my dick. I stroked her hair kindly and that was wrong, though maybe she appreciated it, and then I gave her a twenty, and after a bit she said, "For another twenty I'll sit on it." "You're doing fine." And she was. "Aw come on." "No." "I need money." "Maybe later, when we come back." "You'll drink all your money." "No I won't." "You promise?" "I'm not gonna drink all my money." And then we went downstairs, but before going through the big door, she said she had to leave for a few minutes. Dickhead was sitting by the fire. I told him what was up. He said, "I get to meet the famous Yolanda." He was referring to a December email about her. I wrote group emails about episodes in my life to about a dozen friends. I told him about the blow job, about paying for it. He said, "It's clean that way." I said, "Yeah, it is. Clean. Neat. Tidy." And I wondered if he believed me, if the like was true for him. I doubted it. He was an ex-Marine who lived in a suburban apartment complex of no distinction and once had had, for years, a beautiful Jewish girlfriend whom he'd lost over an Asian massage parlor incident. He was growing thick, early onset of middle-age, and had no girlfriends for a long time now and read my emails on his computer at work, as he didn't have one at home, as, I strongly suspected, he couldn't control himself from jacking off to it all the time. Yolanda came back banging on the steel door and after a minute of chit chat said she had to go to the office. I followed her in so she wouldn't steal but she pulled out the apparatus and the small foil of heroin and went about preparing her fix. My political instinct was to make small talk into a type of counseling, but I didn't. I talked with her about the process, the cleanliness, the purity of the stuff, about how long you can wait, how to decide it's not so hot it burns inside your veins, not so cool it's sluggish through the needle. I told her about my experiences with the stuff, long ago. I exaggerated. I watched her tie off her arm, insert the needle, pull back the syringe so that red blood mixes with the brown liquid of junk. She studied the mix, impatiently jiggled the needle a bit, slowly depressed the plunger. I watched her eyes roll back with a deep deep pleasure of some divine relief. It only lasted a minute. Or less. I told her for me it had lasted a long time. "That's how it starts," she said. I told her I'd decided that the high was so good I resolved to never do it again. "So why can't you quit smoking?" she cracked. She was a bit funny, now and again. Her voice was more the throaty faux-Bronx you heard among certain classes in the Midwest, more that than the sweet south she claimed to have come from. Throughout the night she'd respond to my annoying habit of answering questions with "Huh?" by saying "Hey Dickhead, we'd best buy ol' Tom a hearing aid." We went back downstairs. Talked by the fire. Drank beer and whiskey. Dickhead, being Dickhead, asked what she did for a living. A pair of her panties were on the couch and came up in conversation. How they'd got there I didn't know. Neither did Yolanda. The question didn't interest me, nor her, but Dickhead found it interesting. She didn't like the talk and asked to use Dickhead's cell phone to call her children, to say good night. She hadn't custody. She had nicknames for them, Boopsie and Noodles. Their cousins were over, wherever they were. They called her Aunt Yo Yo. She seemed up on their lives. She hung up, a bit reluctantly. Dickhead, being Dickhead, immediately brought up child abuse. Yolanda said, "Let's change the subject." Dickhead said he wasn't a pedophile, but had a yen for the younger. It was biological, he said. It's all shades of gray, I said. From a nineteen year old with a sixteen year old. A twenty-two year old with a fifteen year old. So on. Eventually it bleeds into sickness and evil. But there was no line. We were human. We had desires. We invented explanations for them. Sometimes you saw you'd drifted to the other side of the line. And sometimes you just had to admit, for a moment at least, that you were evil. But you didn't know how it happened. None of us did. Yolanda was adamant, spoke with passion for seconds. "Twelve years old. That's the line. Before that and you ought to be hung." "You were abused young?" Dickhead said. "If I say Yes will you change the subject," she said. Dickhead wanted to continue the conversation. He'd talked to me recently about a Howard Stern observation: ninety-five percent of hookers, strippers and women doing porn were abused young. I could tell he wanted to bring this up, conduct his own investigation, but I gave him a no-go look, and Yolanda was getting hungry, impatient, pissed that I didn't have soda pop for her, and we left for downtown in Dickhead's ten-year-old Honda immaculately clean, and on the ten-block ride I flashed on being a teeneager, on us all being as teenagers uncoupled off and uncertain and happier than we knew. And we took Yolanda to a place nicer than she was like to have been, the Monkey Bar, had a drink there, upstairs in its loft. Yolanda looked at the menu. It was all appetizers and she wasn't happy about that. "Order 'em all," I said. She wanted a cheeseburger – and dessert. "OK. We'll go somewhere else for food." "OK, let's go." "I'm having a drink here. We'll go." She wasn't a patient woman. John, who owned the bar and liked that I drank and not sipped whiskey and gave downtown color, sat there smirking, looking at Yolanda. You could tell by looking she hadn't in a long long time, if ever, been in a cigar bar that served eleven-dollar raspberry martinis. She was pure faux-Bronx. She looked it, talked it, acted it. He and Dickhead exchanged glances. They were amused in a superior sort of way. John asked how long since she'd lived in the South. She said fifteen years. He said she'd get her accent back in a week, were she to go back. She said it'd take three years. She fidgeted, tugged at my jacket, bebopped in her seat. Her blood was screaming for sugar. She never enjoyed anything. There was that anxiety about the next fix always. There was a new girl behind the bar, a sweet looking young beauty of Asian descent with curves and softness. "What's your name?" I asked. "Tiffany," she said. We chatted. She was studying languages, French and Spanish. Which was very sexy. She was twenty-two, came from Vietnam with her mother when she was nine. "You were born and raised in Vietnam and your name's 'Tiffany'?" "Tremein." She pronounces it exactly between "tremen" and "tremayne". Dickhead, a vet, said, "I knew I knew you from somewhere." We were both captivated by her charm, grace and a certain cheerfulness and were happy she was now working at the bar and we were meeting her, but Yolanda needed attention and we left for Admiral Joe's, walked across the polar parking lots of what had been a busy downtown and made for the corner of Monroe and Tenth. With their every scrunched step, pinched in shoulders, they protested the cold, Dickhead and Yolanda. I didn't. Who knew why. I liked it. I liked walking the urban landscape made desolate by wind and bitter cold. I liked it with Dickhead, the long-haired and extravagantly tattooed ex-Marine, and Yolanda, the hooker junkie. We'd be warm soon enough. But the kitchen was closed at Joe's and we went back to get Dickhead's car and drove to the Big Boy burger chain and went through the drive-through and took the food back to the Monkey Bar and, at the deserted bar in the loft, Yolanda spread out her booty of styrofoam boxes, a whopper cheeseburger, a chef's salad, a cake, ice cream and hot fudge concoction. I liked watching her eat. I remembered the first time, in the dark and cold at my place, she'd sat hunched over the party leftovers while I built a fire, and at the bar, the white fake fur trim of her winter snow hat pulled low over her eyes, auburn hair flaring out, she hunched over her spread of food and commenced wolfing it down. I liked it. Tremein was gone. John was tending bar, amused only because he knew me and not many were in the bar to witness this critter eating from styrofoam on his forty-thousand dollar bartop. It was kinda like show and tell. Yolanda fed me spoonfuls of her dessert. And I liked that, so long as I could pretend that I didn't. But she didn't want to hang out. I did. Dickhead too. We shot pool. Yolanda said she had to leave. She couldn't hang out. The next fix anxiety made her itch, fidget, consumed her attention. Into the cold night she left. We shot pool downstairs, got in a conversation with a guy who'd taken part in archaeological digs in Jerusalem in the 70s. He had no money, though. We bought his drinks. It was a good night. Yolanda showed back up. She was like that, came, went, came back. A yo-yo. You couldn't worry about it. You couldn't help her beyond acceptance. I mean she'd already found Jesus, but she was still fucked. Her life was fucked and I couldn't do anything about it except to every so often put my arm around her shoulder and say. "You're OK. I like you." I'd been cold and lonely and hungry and that could make you angry and hostile and halfways crazy, but what made it good was to then think on the people who'd loved you, recall some moments, and it was OK then, even beautiful, for a while. We went back to my fireplace. Yolanda left. Came back. Left. Dickhead said, "What's she do? Give blow jobs on the street, buy a fix, come back?" The fire was roaring, iron turning red. "I reckon so," I said and was sorry for saying so. Dickhead sat at an old drawing table, sketched like a hint he'd draw Yolanda, preferably without clothes. We drank beer, whiskey. He couldn't draw a line with a ruler. Yolanda reclined on the couch in front of the fire, tidied the blankets, flopped there, dope-woozy a little, said she wanted to take her jeans off, but couldn't with Dickhead there. That was funny – for forty she'd have sucked both our dicks. For eighty she'd have spread her legs with her ass hanging out, but neither of us laughed or said anything because she'd found a moment of dignity and it seemed awfully fragile and after a while, when Dickhead didn't get the meaning of my hard looks, I told him directly and he left, and I crawled into the couch and blankets with a bottle of wine and Yolanda asked if I was ready for the full treatment, and I said OK, and she said forty bucks, and I said I wasn't paying for it, but she was fidgeting again, itching inside her skin and got busy and I didn't protest much, and at one point she raised her head to ask if I'm smoking and I said yes because I was, which I was because I was angry about the money thing, or maybe the whole thing, and she said she guessed that smoking was all right. She slipped a condom on me and got in the straddling position and inches away, her hand guiding me home, she paused and said, "Twenty bucks." I said, "No." She said, "You promised." I said, "I said 'maybe.'" She said, "I need my morning pick me up. Do you want me to get sick." I said, "I took you out. I fed you, paid for everything. It was like a freaking date, except you wander off to the streets every so often to blow strangers." She said, "You drank all your money didn't you." I said yup, though in my pocket I had a fifty and a five. I said, "I've enough for a pack of cigarettes in the morning," and she said, "I knew you would." But then added, pleading, "Come on. You got twenty bucks." I said, "No," but thinking about it. Forget it, Like she can change a fifty, like she'd go get her junk and bring me back the change. I wouldn't eat for two days without that fifty. She hopped off. "Fuck. You bastard. You promised. And you made me waste a condom." I said, "It was my condom." "Bullshit." "Well then we have the same brand." We argued about that, but some of me was laughing inside because I knew somehow all my discomforts I'd sought out. But she wasn't laughing, probably didn't think she'd sought out hers, which made her, in my book, insane, though likely it was the other way around, and she dressed and into the cold night again she went and I lay in the warmth by the fire drinking whiskey now and wondering about her walking the five a.m. streets. She's a mother of two. I closed my eyes, put myself in her shoes, walked the streets with her, looked inside for what happened to the memories, the ideas of hearth, home and family. Try to see what she was seeing. And fell asleep. Then she came back. Bang, Bang, Bang, on the steel door. I let her in and she crawled in behind me, spooned, gently ran her hand through my hair, whispered in my ear, kissed my neck. It was very lovely, and I fell back asleep, and when I woke she was gone and I stayed in bed, a little hungover until I noticed my pants weren't in the position in which I'd tossed them. The fifty was gone. So was the lottery ticket. But the five was still there, which made me laugh a little. How thoughtful. She'd left me enough for a pack of cigarettes. At least she stole without rancor. I dressed and went to the bowl of change on the table because I was thinking with the cigarettes I'd get a newspaper and a cup of coffee, but the bowl was empty. There'd been a lot of change in there. A lot. Pounds and pounds of it. And I thought of Yolanda walking down the street like a Chinese noisemaker, change in all the pockets in which she usually squirreled sweets. I was thinking in my head, imaginarily talking to her, "You took my laundry money, you bitch," but saying it humorously. I was amused while checking Carmen's abandoned stuff for theft. Seemed OK. I'd told Yolanda I'd be damn pissed if she stole anything of Carmen's. That wouldn't be right, I had told her. And she didn't either. But she did steal all my condoms. That was Thursday morning. Friday night I was meeting friends across the river, but stopped downtown first, and was in a good mood, had Tremein on my mind, felt a kind of certainty there that something was gonna happen, something good, for she would be there too, and the feeling would bear out in life, in the course of a long Friday night. I skipped down the stairs to the street and saw a winter coat with hood trimmed in fake white fur hurrying away. I hurried to look down and saw, walking past La Paloma's Mexican Groceries, Yolanda in white on the black of streetlights on black iced sidewalks. "Hey, Yolanda," I bellowed. She kept walking, even maybe hurried more. "YO – YOLANDA – YO YO." She turned to the side, kept going a few more steps – no good news ever hollered after a junkie hooker, especially when passing a door she'd recently exited with stolen booty jiggling in her every pocket. But she stopped after I hollered again. She turned, looked at me. I smiled, raised an open palm, folded it into a peace sign. She didn't respond right away. She stared, moved an arm as if she were about to raise it in greeting, then let it drop, turned and walked into the black beyond the streetlight. I was supposed to follow her – I knew that. But I didn't. I'd stay outside the wizard's gondola only a minute longer, enough for farewells of an inadequate sort. I'd stay another week, another month, then click my heels three times, leave these streets, this life, back into the black and white and I believed that. I turned and went to my truck and to my friends at a bar across the river where they'd want to hear more and not help at all. |

|

© 2004-2010 Underground Voices |

|

|